In this section, we will explore how to use Python as the primary language in IRIS, allowing you to write your application logic in Python while still leveraging the power of IRIS.

How to use it (irispython)

First, let's start by the official way of doing things, which is using the irispython interpreter.

You can use the irispython interpreter to run Python code directly in IRIS. This allows you to write Python code and execute it in the context of your IRIS application.

What is irispython?

irispython is a Python interpreter that is located in the IRIS installation directory (<installation_directory>/bin/irispython), and it is used to run Python code in the context of IRIS.

It will for you:

- Set up the

sys.pathto include the IRIS Python libraries and modules.- This is done by the

site.pyfile, which is located in<installation_directory>/lib/python/iris_site.py. - See the module article Introduction to Python Modules for more details.

- This is done by the

- Allow you to import

irismodules which is a special module that provides access to IRIS features and functionality like bridging any ObjectScript class to Python, and vice versa. - Fix permissions issues and dynamic loading of iris kernel libraries.

Example of using irispython

You can run the irispython interpreter from the command line:

<installation_directory>/bin/irispython

Let's run a simple example:

# src/python/article/irispython_example.py

import requests

import iris

def run():

response = requests.get("https://2eb86668f7ab407989787c97ec6b24ba.api.mockbin.io/")

my_dict = response.json()

for key, value in my_dict.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}") # print message: Hello World

return my_dict

if __name__ == "__main__":

print(f"Iris version: {iris.cls('%SYSTEM.Version').GetVersion()}")

run()

You can run this script using the irispython interpreter:

<installation_directory>/bin/irispython src/python/article/irispython_example.py

You will see the output:

Iris version: IRIS for UNIX (Ubuntu Server LTS for x86-64 Containers) 2025.1 (Build 223U) Tue Mar 11 2025 18:23:31 EDT

message: Hello World

This demonstrates how to use the irispython interpreter to run Python code in the context of IRIS.

Pros

- Python First: You can write your application logic in Python, which allows you to leverage Python's features and libraries.

- IRIS Integration: You can easily integrate your Python code with IRIS features and functionality.

Cons

- Limited Debugging: Debugging Python code in

irispythonis not as straightforward as in a dedicated Python environment.- Don't mean it is not possible, but it is not as easy as in a dedicated Python environment.

- See the bonus section for more details.

- Virtual Environment: It's difficult to set up a virtual environment for your Python code in

irispython.- Doesn't mean it is not possible, but it's difficult to do it due to virtual environment look by default to an interpreter called

pythonorpython3, which is not the case in IRIS. - See the bonus section for more details.

- Doesn't mean it is not possible, but it's difficult to do it due to virtual environment look by default to an interpreter called

Conclusion

In conclusion, using irispython allows you to write your application logic in Python while still leveraging the power of IRIS. However, it has its limitations with debugging and virtual environment setup.

Using WSGI

In this section, we will explore how to use WSGI (Web Server Gateway Interface) to run Python web applications in IRIS.

WSGI is a standard interface between web servers and Python web applications or frameworks. It allows you to run Python web applications in a web server environment.

IRIS supports WSGI, which means you can run Python web applications in IRIS using the built-in WSGI server.

How to use it

To use WSGI in IRIS, you need to create a WSGI application and register it with the IRIS web server.

See the official documentation for more details.

Example of using WSGI

You can find a full template here iris-flask-example.

Pros

- Python Web Frameworks: You can use popular Python web frameworks like Flask or Django to build your web applications.

- IRIS Integration: You can easily integrate your Python web applications with IRIS features and functionality.

Cons

- Complexity: Setting up a WSGI application can be more complex than just using

uvicornorgunicornwith a Python web framework.

Conclusion

In conclusion, using WSGI in IRIS allows you to build powerful web applications using Python while still leveraging the features and functionality of IRIS.

DB-API

In this section, we will explore how to use the Python DB-API to interact with IRIS databases.

The Python DB-API is a standard interface for connecting to databases in Python. It allows you to execute SQL queries and retrieve results from the database.

How to use it

You can install it using pip:

pip install intersystems-irispython

Then, you can use the DB-API to connect to an IRIS database and execute SQL queries.

Example of using DB-API

You use it like any other Python DB-API, here is an example:

# src/python/article/dbapi_example.py

import iris

def run():

# Connect to the IRIS database

# Open a connection to the server

args = {

'hostname':'127.0.0.1',

'port': 1972,

'namespace':'USER',

'username':'SuperUser',

'password':'SYS'

}

conn = iris.connect(**args)

# Create a cursor

cursor = conn.cursor()

# Execute a query

cursor.execute("SELECT 1")

# Fetch all results

results = cursor.fetchall()

for row in results:

print(row)

# Close the cursor and connection

cursor.close()

conn.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

run()

You can run this script using any Python interpreter:

python3 /irisdev/app/src/python/article/dbapi_example.py

You will see the output:

(1,)

Pros

- Standard Interface: The DB-API provides a standard interface for connecting to databases, making it easy to switch between different databases.

- SQL Queries: You can execute SQL queries and retrieve results from the database using Python.

- Remote access: You can connect to remote IRIS databases using the DB-API.

Cons

- Limited Features: The DB-API only provides SQL access to the database, so you won't be able to use advanced IRIS features like ObjectScript or Python code execution.

Alternatives

It also exists a community edition of the DB-API, available here : intersystems-irispython-community.

It has better support of SQLAlchemy, Django, langchain, and other Python libraries that use the DB-API.

See bonus section for more details.

Conclusion

In conclusion, using the Python DB-API with IRIS allows you to build powerful applications that can interact with your database seamlessly.

Notebook

Now that we have seen how to use Python in IRIS, let's explore how to use Jupyter Notebooks with IRIS.

Jupyter Notebooks are a great way to write and execute Python code interactively, and they can be used with IRIS to leverage its features.

How to use it

To use Jupyter Notebooks with IRIS, you need to install the notebook and ipykernel packages:

pip install notebook ipykernel

Then, you can create a new Jupyter Notebook and select the Python 3 kernel.

Example of using Notebook

You can create a new Jupyter Notebook and write the following code:

# src/python/article/my_notebook.ipynb

# Import the necessary modules

import iris

# Do the magic

iris.system.Version.GetVersion()

You can run this notebook using Jupyter Notebook:

jupyter notebook src/python/article/my_notebook.ipynb

Pros

- Interactive Development: Jupyter Notebooks allow you to write and execute Python code interactively, which is great for data analysis and exploration.

- Rich Output: You can display rich output, such as charts and tables, directly in the notebook.

- Documentation: You can add documentation and explanations alongside your code, making

Cons

- Tricky Setup: Setting up Jupyter Notebooks with IRIS can be tricky, especially with the kernel configuration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, using Jupyter Notebooks with IRIS allows you to write and execute Python code interactively while leveraging the features of IRIS. However, it can be tricky to set up, especially with the kernel configuration.

Bonus Section

Starting from this section, we will explore some advanced topics related to Python in IRIS, such as remote debugging Python code, using virtual environments, and more.

Most of these topics are not officially supported by InterSystems, but they are useful to know if you want to use Python in IRIS.

Using a native interpreter (no irispython)

In this section, we will explore how to use a native Python interpreter instead of the irispython interpreter.

This allows you to use virtual environments out of the box, and to use the Python interpreter you are used to.

How to use it

To use a native Python interpreter, you to have IRIS install locally on your machine, and you need to have the iris-embedded-python-wrapper package installed.

You can install it using pip:

pip install iris-embedded-python-wrapper

Next, you need to setup some environment variables to point to your IRIS installation:

export IRISINSTALLDIR=<installation_directory>

export IRISUSERNAME=<username>

export IRISPASSWORD=<password>

export IRISNAMESPACE=<namespace>

Then, you can run your Python code using your native Python interpreter:

python3 src/python/article/irispython_example.py

# src/python/article/irispython_example.py

import requests

import iris

def run():

response = requests.get("https://2eb86668f7ab407989787c97ec6b24ba.api.mockbin.io/")

my_dict = response.json()

for key, value in my_dict.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}") # print message: Hello World

return my_dict

if __name__ == "__main__":

print(f"Iris version: {iris.cls('%SYSTEM.Version').GetVersion()}")

run()

For more details, see the iris-embedded-python-wrapper documentation.

Pros

- Virtual Environments: You can use virtual environments with your native Python interpreter, allowing you to manage dependencies more easily.

- Familiar Workflow: You can use the Python interpreter you are used to, making it easier to integrate with your existing workflows.

- Debugging: You can use your favorite Python debugging tools, such as

pdboripdb, to debug your Python code in IRIS.

Cons

- Setup Complexity: Setting up the environment variables and the

iris-embedded-python-wrapperpackage can be complex, especially for beginners. - Not Officially Supported: This approach is not officially supported by InterSystems, so you may encounter issues that are not documented or supported.

DB-API Community Edition

In this section, we will explore the community edition of the DB-API, which is available on GitHub.

How to use it

You can install it using pip:

pip install sqlalchemy-iris

Which will install the community edition of the DB-API.

Or with a specific version:

pip install https://github.com/intersystems-community/intersystems-irispython/releases/download/3.9.3/intersystems_iris-3.9.3-py3-none-any.whl

Then, you can use the DB-API to connect to an IRIS database and execute SQL queries or any other Python code that uses the DB-API, like SQLAlchemy, Django, langchain, pandas, etc.

Example of using DB-API

You can use it like any other Python DB-API, here is an example:

# src/python/article/dbapi_community_example.py

import intersystems_iris.dbapi._DBAPI as dbapi

config = {

"hostname": "localhost",

"port": 1972,

"namespace": "USER",

"username": "_SYSTEM",

"password": "SYS",

}

with dbapi.connect(**config) as conn:

with conn.cursor() as cursor:

cursor.execute("select ? as one, 2 as two", 1) # second arg is parameter value

for row in cursor:

one, two = row

print(f"one: {one}")

print(f"two: {two}")

You can run this script using any Python interpreter:

python3 /irisdev/app/src/python/article/dbapi_community_example.py

Or with sqlalchemy:

from sqlalchemy import create_engine, text

COMMUNITY_DRIVER_URL = "iris://_SYSTEM:SYS@localhost:1972/USER"

OFFICIAL_DRIVER_URL = "iris+intersystems://_SYSTEM:SYS@localhost:1972/USER"

EMBEDDED_PYTHON_DRIVER_URL = "iris+emb:///USER"

def run(driver):

# Create an engine using the official driver

engine = create_engine(driver)

with engine.connect() as connection:

# Execute a query

result = connection.execute(text("SELECT 1 AS one, 2 AS two"))

for row in result:

print(f"one: {row.one}, two: {row.two}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

run(OFFICIAL_DRIVER_URL)

run(COMMUNITY_DRIVER_URL)

run(EMBEDDED_PYTHON_DRIVER_URL)

You can run this script using any Python interpreter:

python3 /irisdev/app/src/python/article/dbapi_sqlalchemy_example.py

You will see the output:

one: 1, two: 2

one: 1, two: 2

one: 1, two: 2

Pros

- Better Support: It has better support of SQLAlchemy, Django, langchain, and other Python libraries that use the DB-API.

- Community Driven: It is maintained by the community, which means it is more likely to be updated and improved over time.

- Compatibility: It is compatible with the official InterSystems DB-API, so you can switch between the official and community editions easily.

Cons

- Speed: The community edition may not be as optimized as the official version, potentially leading to slower performance in some scenarios.

Debugging Python Code in IRIS

In this section, we will explore how to debug Python code in IRIS.

By default, debugging Python code in IRIS (in objectscript with the language tag or %SYS.Python) is not possible, but a community solution exists to allow you to debug Python code in IRIS.

How to use it

First install IoP Interoperability on Python:

pip install iris-pex-embedded-python

iop --init

This will install IoP and new ObjectScript classes that will allow you to debug Python code in IRIS.

Then, you can use the IOP.Wrapper class to wrap your Python code and enable debugging.

Class Article.DebuggingExample Extends %RegisteredObject

{

ClassMethod Run() As %Status

{

set myScript = ##class(IOP.Wrapper).Import("my_script", "/irisdev/app/src/python/article/", 55550) // Adjust the path to your module

Do myScript.run()

Quit $$$OK

}

}

Then configure VsCode to use the IoP debugger by adding the following configuration to your launch.json file:

{

"version": "0.2.0",

"configurations": [

{

"name": "Python in IRIS",

"type": "python",

"request": "attach",

"port": 55550,

"host": "localhost",

"pathMappings": [

{

"localRoot": "${workspaceFolder}/src/python/article",

"remoteRoot": "/irisdev/app/src/python/article"

}

]

}

]

}

Now, you can run your ObjectScript code that imports the Python module, and then attach the debugger in VsCode to the port 55550.

You can run this script using the following command:

iris session iris -U IRISAPP '##class(Article.DebuggingExample).Run()'

You can then set breakpoints in your Python code, and the debugger will stop at those breakpoints, allowing you to inspect variables and step through the code.

Video of remote debugging in action (for IoP but the concept is the same):

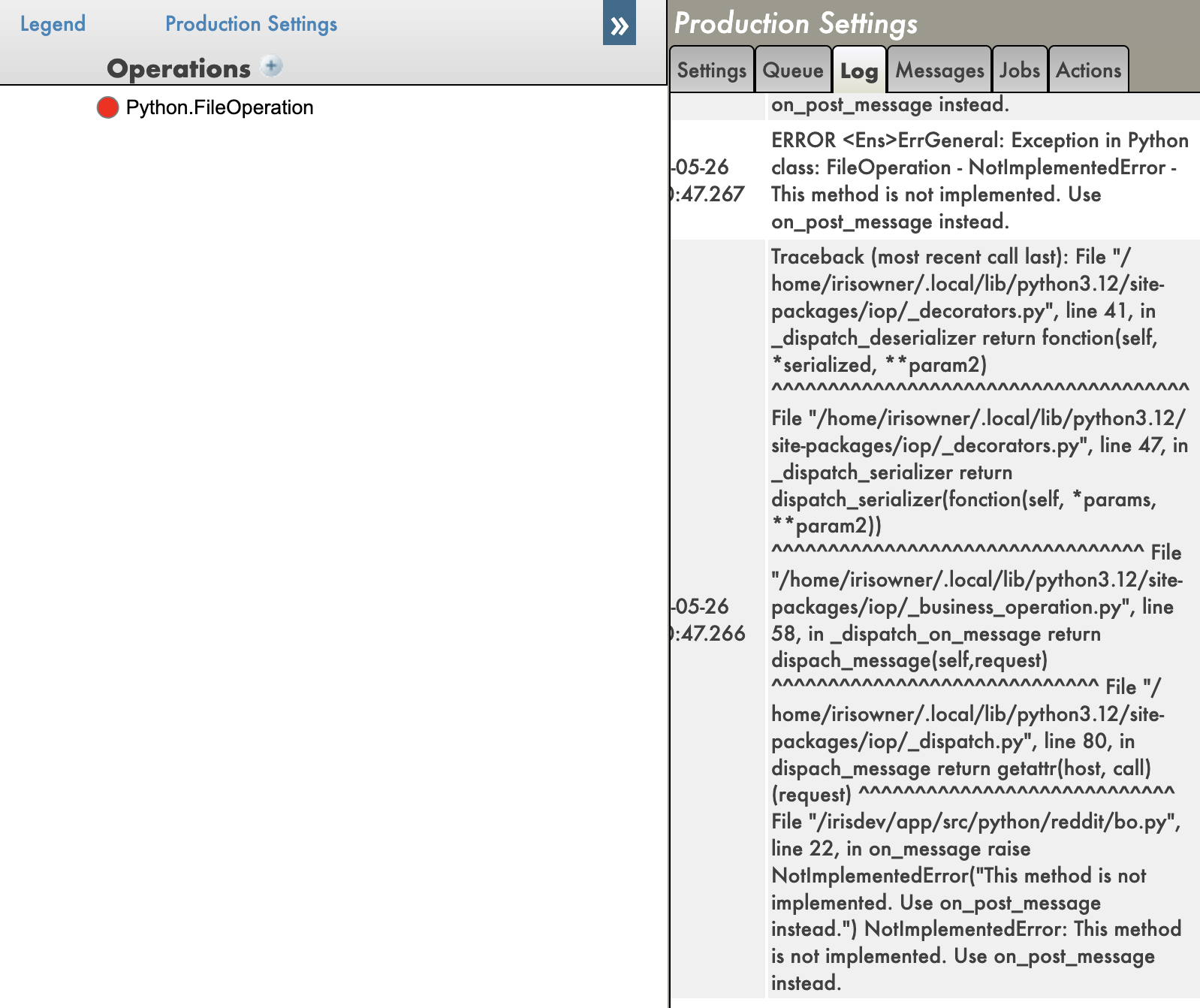

And you have also tracebacks in your Python code, which is very useful for debugging.

With tracebacks enabled:

With tracebacks disabled:

Pros

- Remote Debugging: You can debug Python code running in IRIS remotely, which is IMO a game changer.

- Python Debugging Features: You can use all the Python debugging features, such as breakpoints, variable inspection, and stepping through code.

- Tracebacks: You can see the full traceback of errors in your Python code, which is very useful for debugging.

Cons

- Setup Complexity: Setting up the IoP and the debugger can be complex, especially for beginners.

- Community Solution: This is a community solution, so it may not be as stable or well-documented as official solutions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, debugging Python code in IRIS is possible using the IoP community solution, which allows you to use the Python debugger to debug your Python code running in IRIS. However, it requires some setup and may not be as stable as official solutions.

IoP (Interoperability on Python)

In this section, we will explore the IoP (Interoperability on Python) solution, which allows you to run Python code in IRIS in a python-first approach.

I have been developing this solution for a while now, this is my baby, it tries to solve or enhance all the previous points we have seen in this series of articles.

Key points of IoP:

- Python First: You can write your application logic in Python, which allows you to leverage Python's features and libraries.

- IRIS Integration: You can easily integrate your Python code with IRIS features and functionality.

- Remote Debugging: You can debug your Python code running in IRIS remotely.

- Tracebacks: You can see the full traceback of errors in your Python code, which is very useful for debugging.

- Virtual Environments: You have a support of virtual environments, allowing you to manage dependencies more easily.

To learn more about IoP, you can check the official documentation.

Then you can read those articles to learn more about IoP:

🐍❤️ As you can see, IoP provides a powerful way to integrate Python with IRIS, making it easier to develop and debug your applications.

You don't need to use irispython anymore, you don't have to set your sys.path manually, you can use virtual environments, and you can debug your Python code running in IRIS.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this series of articles about Python in IRIS.

Feel free to reach out to me if you have any questions or feedback about this series of articles.

GL HF with Python in IRIS!

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)